When you find an investment strategy that has worked in the past, how do you know it will work in the future? We may just be overconfident. • Traders tend to select strategies that have had a ‘hot streak’ recently, but those formulas may have a ‘cold streak’ for the next few years. Simple strategies are likely to perform better over the long run than complex strategies that are ‘curve fit.’

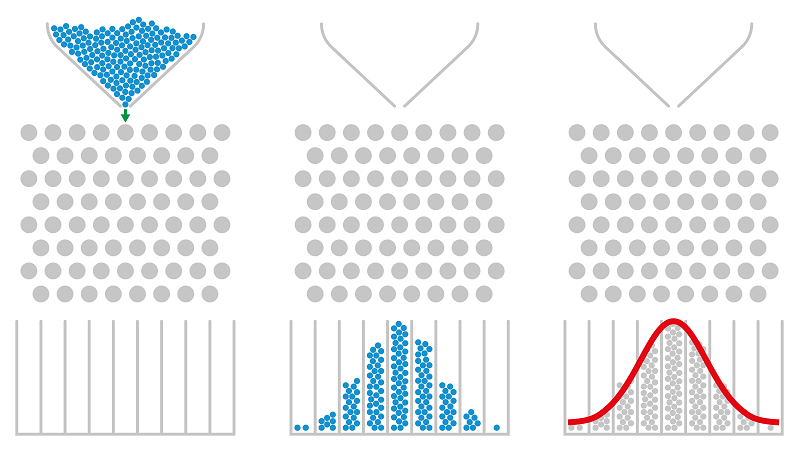

Figure 1. When we backtest hundreds of strategies, some will show great returns and others poor returns — with most in the middle — completely at random, resulting in a bell curve. Illustration of Galton board by Peter Hermes Furian/Shutterstock.

• Part 2 of a series. Part 1 appeared on Mar. 5, 2019. •

As we’ve seen, our brains can make objects seem to be colors that they are not (when measured by instruments). This is just one of many ways that our minds trick us. We say, “I’m certain, I saw it with my own eyes,” when something entirely different is actually happening.

Seeing what the brain wants us to see is not limited to images on a page or on a screen. The mind makes us perceive things all the time that we’re sure are real but are just products of our imagination.

Numerous studies have demonstrated that magnetic stimulation of portions of the brain can make people see or sense a “ghostly apparition.” Since we’re exposed to magnetic fields all the time, some psychologists believe this brain interaction explains many cases of “haunting” or out-of-body experiences. One professional who designed such experiments was Michael Persinger, Ph.D., of Laurentian University, who unfortunately passed away last year. (See Persinger, et al., 2000.)

Lessons in probability for investors

In the field of investing, there are many behaviors we’re not aware of that affect our decision-making abilities. One example is that investors tend to have an illusion of control. This is all the more dangerous because we’re not conscious of it.

One study showed that subjects who were asked to bet on a coin toss would wager larger sums if the subjects could call “heads” or “tails” before a lab assistant flipped the coin (instead of after, but before the outcome was shown). The only explanation is that people unconsciously believe they can somehow will the coin to be more likely to come up heads or tails. This is the illusion of control. We all have it, whether or not we recognize its influence on our decisions.

Other experiments with coin-tossing games show:

- People exhibit more risk-taking behavior after experiencing a loss (thinking that a loss somehow makes a win more probable);

- Players are influenced by the views of lucky-guessing “coin-toss experts” after witnessing just a few correct calls; and

- Players’ bets on heads or tails go down after a short streak of one or the other. (See Gambler’s Fallacy.)

A good book on these “behavioral biases” is Your Money and Your Brain — which recently came out in a new paperback edition — by Wall Street Journal columnist Jason Zweig.

The challenge of technical analysis

It’s important to remember that being aware of behavioral biases does not mean we can stop them from affecting us. Our minds work at subconscious levels that intellectual analysis cannot overcome.

The most important impact on investors lies in the field of technical analysis: the use of price, volume, and other data to make buy and sell decisions.

A massive study of buy-sell logic makes up the meat of the book Evidence-Based Technical Analysis. Its author, David Aronson, worked for Spear, Leeds & Kellogg as a trader before joining Baruch College in New York as an adjunct professor of technical analysis.

In a gargantuan task, Aronson backtested more than 6,400 trading rules over 25 years, November 1980 through June 2005. That period should be long enough to reveal at least some interesting patterns.

Indeed, about 5% of the tested rules did excel — and with statistical significance, by the usual measures. However, this was before Aronson compensated for data-mining bias. Traders often don’t realize that the more backtests they run, the more likely it is that the better-performing alternatives will rise to the top through random chance. This is also known as “curve fitting.” It works much the same way as the so-called Galton board, which is illustrated in Figure 1. By chance, some balls that bounce through the maze will wind up with very low scores (in the far left pocket) and very high scores (on the far right).

Aronson corrected for his experiment’s data-mining bias by running Monte Carlo Permutations and White’s Reality Check, two widely used statistical tools. He calculated that at least one rule, by random chance, should have resulted in an 11% annualized stock-market return. But the “best” rule in the experiment returned only 10.25%. The winners and losers in the game were distributed randomly in a bell curve — just like the balls on a Galton board! Many things about the stock market don’t follow a bell curve. However, highly random events like trading returns do. (See Aronson’s excerpt.)

But don’t despair! Another exhaustive series of tests examined almost 40,000 trading rules. In the next part of this series, we’ll see what worked.

• Parts 3 and 4 appear on Mar. 12 and 14, 2019.

UPDATE 2019-04-04: I published a follow-up article about an inexpensive device that visually exhibits bell-curve behavior. See my Apr. 4, 2019 column.

With great knowledge comes great responsibility.

—Brian Livingston

Send story ideas to MaxGaines “at” BrianLivingston.com