Bogle’s secret in building America’s largest fund provider is setting it up from the beginning as a ‘mutual’ organization, similar to a worker’s cooperative. • Vanguard doesn’t own its funds, the funds own Vanguard and can make the firm lower its fees to benefit investors. It’s a hilarious irony that Vanguard’s socialist model has beaten Wall Street’s wealth-management firms at their own game.

Figure 1. A life-size statue of Jack Bogle stands on the Vanguard corporate campus in Malvern, Pennsylvania. Photo by Blair duQuesnay/The Belle Curve.

• Parts 1 and 2 of this column appeared on Jan. 15 and 17, 2019.

The Vanguard Group became the largest fund provider in the US — and the second largest asset manager of any kind in the world (after BlackRock) — by constantly driving down the fees investors had to pay. But how was it possible for the upstart organization to cut its costs in a way that most wealth managers couldn’t duplicate?

The answer, as described in Jack Bogle’s December 2018 book Stay the Course, is that he talked the board of directors in 1974 into forming the company as a “mutual” organization. This structure is used by some insurance groups — Mutual of Omaha being a famous example — but Vanguard is the only wealth manager to use it, according to the book. (One arguable exception is TIAA, a major financial-services organization that operates as a nonprofit corporation.)

Structured like a cooperative for investors, Vanguard’s mutual funds and ETFs hold the reins. In a very legal sense, Vanguard does not own its funds and cannot insist they raise their fees to provide more for the parent company’s bottom line. Instead, the funds own Vanguard. So far, the funds have managed to drive costs for investors lower and lower, continuing even 45 years after Bogle launched the firm.

A constant battle to lower its own costs

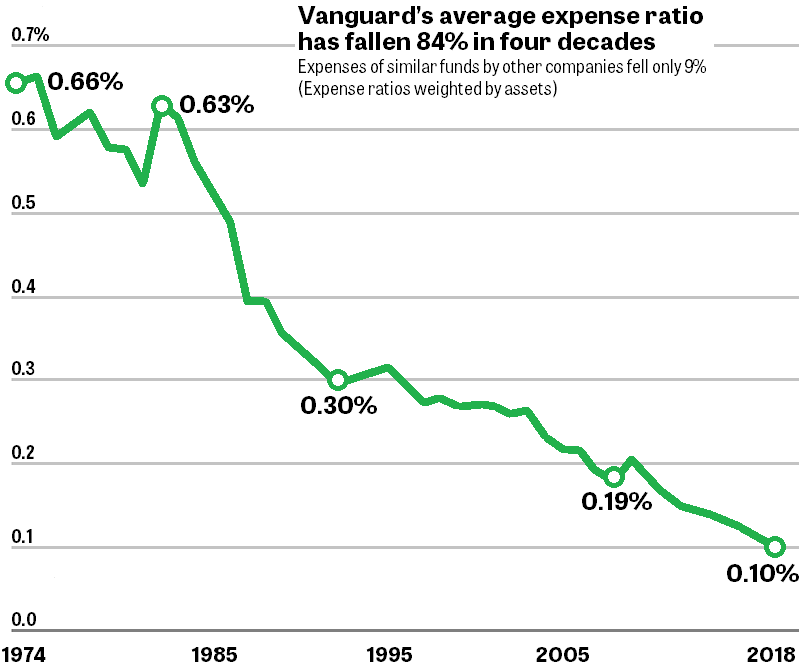

Today, Vanguard’s average expense ratio (annual fee) — determined by weighting the assets of each fund — is a low, low 0.10%. What many people don’t realize is that Vanguard didn’t start out at that bargain-basement level. It worked its way to the very height of the low-fee providers.

Figure 2. Vanguard lowered its fees almost every year until Bogle resigned as CEO for health reasons in 1996 — and then the firm lowered the fees even more. Source: Vanguard and the Strategic Insight Simfund.

Figure 2, based on a graph from Bogel’s book, shows that today’s rock-bottom Vanguard fees required a continuous effort to reduce costs wherever possible. The average fund’s expense ratio was 0.66% when Bogle founded Vanguard. The rate had dropped below 0.30% by the time Bogle resigned as Vanguard’s CEO in 1996. In small steps, the company whittled its expenses all the way down to 0.10% as of 2018. On every $100 invested, the average Vanguard fund owner pays only 10 cents per year.

The competition has a hard time catching up (or down)

Why don’t other providers of mutual funds and ETFs simply match Vanguard’s rates? They’re trying. Especially in the highly visible products that are S&P 500 index ETFs, there truly is a price war. Schwab’s SCHX and State Street’ SPLG both track US large-caps but not strictly the S&P 500. They boast annual fees of only 0.03%. That compares favorably with Vanguard’s VOO, an S&P 500 tracking fund, whose 0.04% fee was formerly the lowest. The difference between 0.03% and 0.04% is miniscule and hardly worth fretting about. Meanwhile, State Street’s own SPY — the world’s most frequently traded security of any kind — sticks with its much-higher 0.09% fee.

Other asset classes that aren’t such stars make Vanguard’s built-in price advantage really shine. Since Vanguard operates essentially “at-cost” — most profits are used to reduce prices for members/investors — Wall Street firms with constant earnings pressure and high overhead can’t match Vanguard’s low rates.

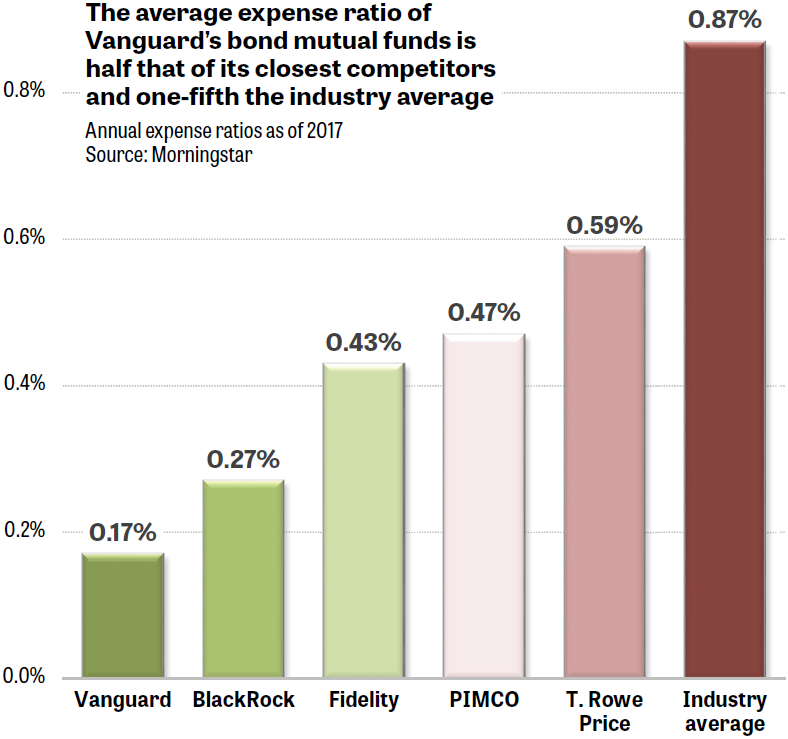

Figure 3. Despite their best attempts, other companies can’t match Vanguard’s low fees in asset classes other than the most heavily traded large-cap equity funds.

Nowhere is this more clear than with bond funds. No matter how much people may like to trade, everyone eventually has to hold some bonds, even if only to park funds in a safe haven for a while, hold a house down payment until the close, dampen the crash-prone nature of an equity-only portfolio, or whatever.

Figure 3 shows how this translates into fees for bond funds. Even the firms that are racing to catch Vanguard on price — BlackRock, Fidelity, PIMCO, and T. Rowe Price — routinely charge annnual fees that are two to three times those of the Pennsylvania company.

When you look at the entire universe of bond mutual funds, several of them charge even more, driving up the industry average. Vanguard’s bond funds charge only 20% of the weighted average of all other such funds.

I'm telling you all this because it’s easy for us to say, “Fees matter,” but it’s sometimes hard to truly grasp what a big difference fees make.

People sometimes mistakenly assume I must be taking kickbacks from Vanguard, because the strategies in Muscular Portfolios that I “cloned” from Jack Bogle, Mebane Faber, and Steve Le Compte specify a number of Vanguard ETFs. In reality, I receive nothing from Vanguard. When I was writing the book, Vanguard simply offered the best matches for the asset classes the various strategies used. Equally important, the firm’s fees were the most attractive of any provider’s.

That doesn’t mean everyone should use only Vanguard funds. The giant company offers no mutual funds or ETFs that track commodities or precious metals, both of which went up when the S&P 500 was crashing in 2007–2008. And its selection of cash-like fixed-income funds is weak. For example, Vanguard’s money-market mutual fund, VMRXX, requires a minimum investment of $10,000.

In cases like these, I’m happy to recommend other products, such as Invesco’s PDBC, iShares’s IAU, and State Street’s BIL, respectively. And if any firm invents financial vehicles with better performance, lower fees, or greater tax-efficiency than Vanguard’s, I’ll report to you on those, too.

Where’d my yield get up and go? Went out with the fees

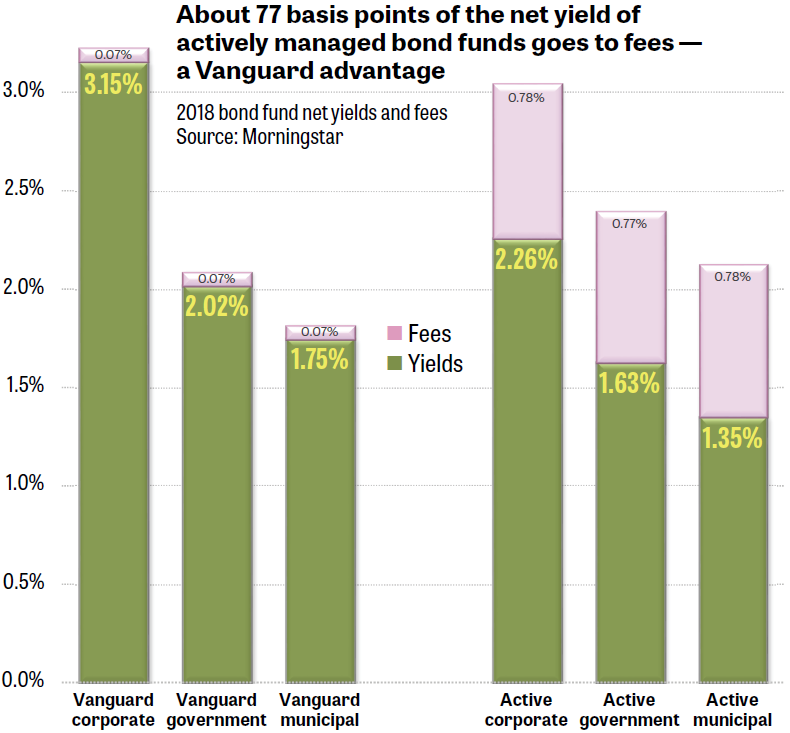

The higher expenses ratios that Vanguard’s would-be competitors charge really show up when you’re holding a bond fund. Figure 4 illustrates how much these fees can eat up the yield you were expecting — even when those fees are well below the 1% level that many investors think is “nothing.”

Figure 4. Actively managed bond mutual funds can sometimes offer good performance, but not after fees.

As of 2018, statistics from Morningstar indicate that Vanguard’s corporate bond funds provide a higher yield than other companies’ managed corporate bond funds (3.15% vs. 2.26%). That relationship is true whether or not each fund’s annual fees are subtracted.

It’s a different story when you consider government and muni bond funds. The managers of those portfolios actually eke out higher gross yields than Vanguard’s funds in those two categories. But the excess yield all goes away — and more — after subtracting those managers’ fees. A headwind of 0.77 or 0.78 percentage points drives their yields significantly below Vanguard’s simple funds, which merely hold every bond that fits into a particular asset class (corporate, governmental, or municipal).

The lesson is simple: pay close attention to the fees of the financial products and services you buy. A number like 1% can be deceptive:

- If you leave a tip of only 1% for a restaurant server, that’s very little.

- If a financial provider is charging you 1% of your life savings each year, that’s a lot.

In the fourth and final part of this column, we’ll learn other secrets from Bogle’s last book and how we can apply them to realize greater profits for ourselves.

• Part 4 appears on Jan. 24, 2019.

With great knowledge comes great responsibility.

—Brian Livingston

Send story ideas to MaxGaines “at” BrianLivingston.com